The Summer I Learned to Sail

An anecdote

The first time I skippered a sailboat, I possessed a small amount of theoretical sailing knowledge, and even less practical experience on the water. My sailboat-loving father had optimistically enrolled my two sisters and me in an intermediate-level sailing course and then took us out one time to impart the basics of boating.

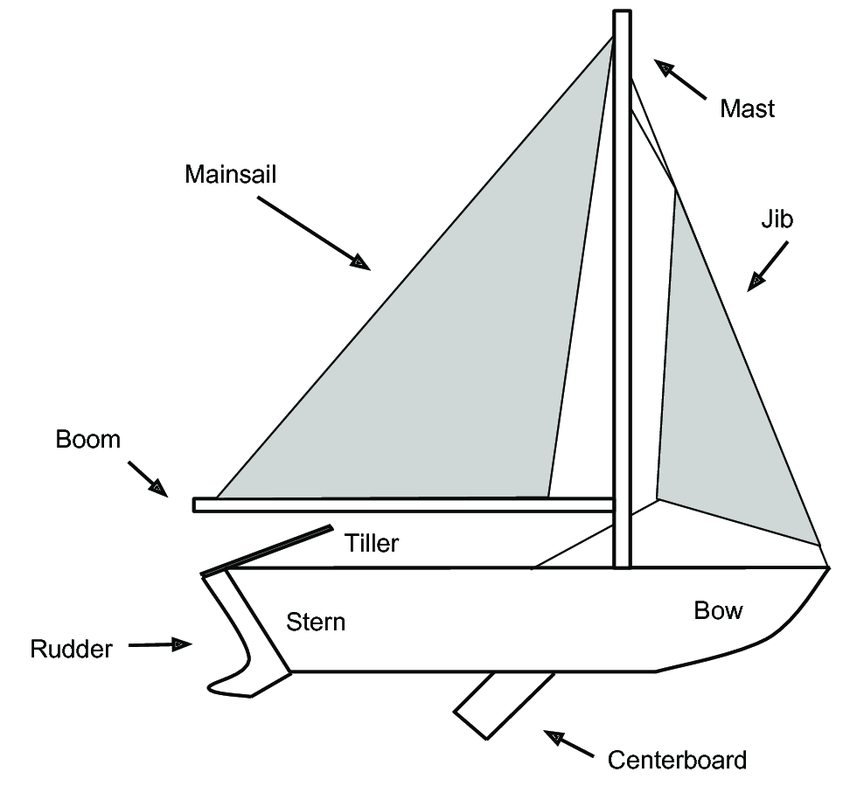

The craft of choice for this course was not one of those imposing sailboats you might imagine on the lake or bay, with a steering wheel and even a cabin below deck, but rather its baby sibling - a two-person sailboat called the 420. To avoid getting caught up in the weeds (or irons1) of sailing lingo, I offer you this humble sailboat diagram, which contains just enough information to get us all through my nautical anecdote.

The 420, which Wikipedia now arrogantly claims is a “dinghy,” fits two sailors who play separate roles: skipper and crew. The skipper handles the main sheet (the rope that controls the mainsail), as well as the tiller. To turn the boat left, you push the tiller right, and vice versa. Serving as the skipper requires concentration and the ability to multitask – you only have two hands after all, and both hands have separate jobs. Your eyes, and by extension your brain, have yet another job. You watch the wind in the sail, adjust the main sheet with one hand, and push the tiller with the other. When you tack or jibe (aka turn), you scoot under the boom and switch sides, and now your hands have switched jobs. The crew member, by comparison, has a simpler but still significant job: man the jib sheet (the rope that controls the jib) and act as extra weight on whatever side of the boat needs settling.

The two sailors are supposed to work in tandem, and a good working relationship between the skipper and crew makes all the difference. A crew member who turns off his or her brain and only moves when asked by the skipper is rather like a husband who says, “Of course I can help out around the house – just make me a list of what needs to be done.”2

On the first day at the dock, I tried to ignore my pitiable amateur status and assured the little voice inside that the other students should have the requisite skills – and every boat held two people. I could happily handle the jib while another student showed me the ropes – er, sheets. God laughed at my plans, however, and my newly assigned partner immediately volunteered to serve as crew, my hoped-for out. No amount of explanation that I, in fact, did not know how to sail waylaid her desire to avoid being the captain of our little boat.

So there I was: a beginner sailor in an intermediate course, promoted prematurely to the role of skipper. I feared neither sinking nor drowning – stakes were not quite that high – but every other consequence of my expected future failure felt quite real – and imminent. Boats do capsize. The boom can and will whack into anyone too slow to duck. And while a dunk in the cold bay water wouldn’t kill me, I had my suspicions about it being a generally pleasant experience. At fourteen years old, I defaulted to my tried-and-true method of dealing with things that made me anxious: find someone older or wiser to do it for me. Instead, I found another teenager, the same age as me and much less (I would learn over the following days) wise. Someone had to take charge and it turns out that when my first default flounders, my next recourse involves sighing dramatically and doing it myself.3 Before I had much time to process, we were out on the water, surrounded by other sailboats, and I found myself hoping that their captains, at least, had been sailing more than one time before.

For the rest of that day, for the next two weeks, my mind was consumed with the art of sailing. Every morning, in sun and wind and rain, we showed up at that dock and stepped aboard some sailboats. We unfurled sails and tied knots and then set everything back to rights at the end of the day. Now and then I got a blessed break as crew, but I spent most of my time at the tiller. And I learned. Boy did I learn. My parents always told me that the best way to master a new language is through total immersion, and it turns out that it’s also the best way to master (or at least intermediate-er) sailing.

Those two weeks of sails and saltwater challenged me. The days left me physically tired and mentally drained, but the hours spent making and recovering from silly mistakes forced me into greater confidence and skill. Soon I could hold my own with the other students, and together we learned new tricks, including one called a roll tack, which is a type of turn wherein you push your boat to the point of almost tipping over, to reduce loss of speed on the turn. We also learned the follow-up technique: how to get your sailboat back upright after you get so close to capsizing that you just actually capsize.4

It has been more than a decade since that sailing course, and about that long since I’ve had a proper sailing jaunt, but I still remember the feeling of skimming across the water, sails full and hull lifting as we picked up speed. At first, I would have felt fear, and given slack to the main sheet, restoring balance to the boat, but slowing us down. After some time, though, I grew confident enough to welcome the pace and slip my feet into the black straps attached to the deck. Called hiking straps, these strips of canvas allow a sailor to remain secure while leaning his or her entire body over the edge of the boat, giving enough counterbalance to keep things steady. It may seem counterintuitive - practically throwing yourself overboard to keep the boat steady - but it feels like flying.

I don’t want to go overboard (pun intended) trying to make this fun memory into a lesson, but there are pieces of the story that remind me even now – life offers us a lot of chances to feel like a beginner amongst more accomplished fellows. It may not be on a boat dock or open water, but a room full of strangers can feel just as intimidating. Maybe sometimes those others – like my former crewmember – are winging it right along with you.

But then maybe sometimes you’re right and you are a beginner, and most (if not all) of those around you are more skilled and more comfortable. Surely some of the students in my course came in with the requisite level of experience, but so what? Life doesn’t have rubrics, and there is no benchmark of skills you must possess for the right to try something new. And no amount of practice gets you past the point of making a mistake now and again. The other sailors in my class – the actual intermediate-level students – capsized their boats alongside the rest of us imposters. We all ended up in the water at some point.

Look, all I’m trying to say is that your fear of ending up swimming alongside an upturned boat shouldn’t keep you from going out in the first place. There is value in knowing our limits and avoiding unfounded pride, but aren’t some forms of anxiety or self-consciousness also just pride at their root? On the one end, you can get too caught up in your own achievements, but it’s possible to do the same in the other direction, fixating on your own failings to the point of debilitation, convincing yourself that you are uniquely restricted by these fears in a way that others are not. We’re all a little scared (I am at least) but I think that’s a sign of doing something worthwhile. Life begins, as they say,5 at the end of your comfort zone.

#boathumor, I’m so sorry

Maybe I can write “sailing as an analogy for an egalitarian marriage” later. Point 1) Define your terms. Looking at you, Mr. Sailing Assistant who yelled at me while docking, “push away means push away!” Push what away? The boat or the tiller?? I’m not a mind reader.

yes, the sighing part is essential.

To do this, you have to climb onto the centerboard, and then use your body weight to heave the boat back to vertical. As the boat returns to the upright position, you desperately attempt to jump back into the boat before you end up back in the water.

“They” being Neale Donald Walsch, apparently

This was fun! And I loved the last part about pride. Reminds me of this quote from Mere Christianity:

“Do not imagine that if you meet a really humble man he will be what most people call 'humble' nowadays: he will not be a sort of greasy, smarmy person, who is always telling you that, of course, he is nobody.

Probably all you will think about him is that he seemed a cheerful, intelligent chap who took a real interest in what you said to him.

If you do dislike him it will be because you feel a little envious of anyone who seems to enjoy life so easily. He will not be thinking about humility: he will not be thinking about himself at all.”

OMG Jessica the “just make me a list” has me in stitches